Pascal's triangle

In mathematics, Pascal's triangle is a triangular array of the binomial coefficients in a triangle. It is named after the French mathematician, Blaise Pascal. It is known as Pascal's triangle in much of the Western world, although other mathematicians studied it centuries before him in India, Persia, China, Germany, and Italy.[1]

The rows of Pascal's triangle are conventionally enumerated starting with row n = 0 at the top. The entries in each row are numbered from the left beginning with k = 0 and are usually staggered relative to the numbers in the adjacent rows. A simple construction of the triangle proceeds in the following manner. On row 0, write only the number 1. Then, to construct the elements of following rows, add the number directly above and to the left with the number directly above and to the right to find the new value. If either the number to the right or left is not present, substitute a zero in its place. For example, the first number in the first row is 0 + 1 = 1, whereas the numbers 1 and 3 in the third row are added to produce the number 4 in the fourth row.

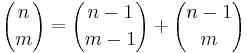

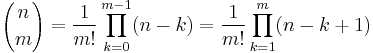

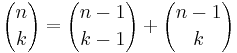

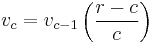

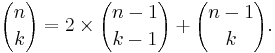

This construction is related to the binomial coefficients by Pascal's rule, which says that if

then

for any nonnegative integer n and any integer k between 0 and n.[2]

Pascal's triangle has higher dimensional generalizations. The three-dimensional version is called Pascal's pyramid or Pascal's tetrahedron, while the general versions are called Pascal's simplices.

Contents |

History

The set of numbers that form Pascal's triangle were well known before Pascal. However, Pascal developed many applications of it and was the first one to organize all the information together in his treatise, Traité du triangle arithmétique (1653). The numbers originally arose from Hindu studies of combinatorics and binomial numbers and the Greeks' study of figurate numbers.[3]

The earliest explicit depictions of a triangle of binomial coefficients occur in the 10th century in commentaries on the Chandas Shastra, an Ancient Indian book on Sanskrit prosody written by Pingala in or before the 2nd century BC.[4] While Pingala's work only survives in fragments, the commentator Halayudha, around 975, used the triangle to explain obscure references to Meru-prastaara, the "Staircase of Mount Meru". It was also realised that the shallow diagonals of the triangle sum to the Fibonacci numbers. In 1068, four columns of the first sixteen rows were given by the mathematician Bhattotpala, who realized the combinatorial significance.[4]

At around the same time, it was discussed in Persia (Iran) by the Persian mathematician, Al-Karaji (953–1029).[5] It was later repeated by the Persian poet-astronomer-mathematician Omar Khayyám (1048–1131); thus the triangle is referred to as the Khayyam-Pascal triangle or simply the Khayyam triangle in Iran. Several theorems related to the triangle were known, including the binomial theorem. Khayyam used a method of finding nth roots based on the binomial expansion, and therefore on the binomial coefficients.

In 13th century, Yang Hui (1238–1298) presented the arithmetic triangle that is the same as Pascal's triangle. Pascal's triangle is called Yang Hui's triangle in China.[6] The "Yang Hui's triangle" was known in China in the early 11th century by the Chinese mathematician Jia Xian (1010-1070).

Petrus Apianus (1495–1552) published the triangle on the frontispiece of his book on business calculations in the 16th century. This is the first record of the triangle in Europe.

In Italy, it is referred to as Tartaglia's triangle, named for the Italian algebraist Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia (1500–77). Tartaglia is credited with the general formula for solving cubic polynomials, (which may in fact be from Scipione del Ferro but was published by Gerolamo Cardano 1545).

Pascal's Traité du triangle arithmétique (Treatise on Arithmetical Triangle) was published posthumously in 1665. In this, Pascal collected several results then known about the triangle, and employed them to solve problems in probability theory. The triangle was later named after Pascal by Pierre Raymond de Montmort (1708) who called it "Table de M. Pascal pour les combinaisons" (French: Table of Mr. Pascal for combinations) and Abraham de Moivre (1730) who called it "Triangulum Arithmeticum PASCALIANUM" (Latin: Pascal's Arithmetic Triangle), which became the modern Western name.[7]

Binomial expansions

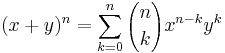

Pascal's triangle determines the coefficients which arise in binomial expansions. For an example, consider the expansion

- (x + y)2 = x2 + 2xy + y2 = 1x2y0 + 2x1y1 + 1x0y2.

Notice the coefficients are the numbers in row two of Pascal's triangle: 1, 2, 1. In general, when a binomial like x + y is raised to a positive integer power we have:

- (x + y)n = a0xn + a1xn−1y + a2xn−2y2 + ... + an−1xyn−1 + anyn,

where the coefficients ai in this expansion are precisely the numbers on row n of Pascal's triangle. In other words,

This is the binomial theorem.

Notice that the entire right diagonal of Pascal's triangle corresponds to the coefficient of yn in these binomial expansions, while the next diagonal corresponds to the coefficient of xyn−1 and so on.

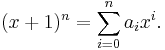

To see how the binomial theorem relates to the simple construction of Pascal's triangle, consider the problem of calculating the coefficients of the expansion of (x + 1)n+1 in terms of the corresponding coefficients of (x + 1)n (setting y = 1 for simplicity). Suppose then that

Now

The two summations can be reorganized as follows:

(because of how raising a polynomial to a power works, a0 = an = 1).

We now have an expression for the polynomial (x + 1)n+1 in terms of the coefficients of (x + 1)n (these are the ais), which is what we need if we want to express a line in terms of the line above it. Recall that all the terms in a diagonal going from the upper-left to the lower-right correspond to the same power of x, and that the a-terms are the coefficients of the polynomial (x + 1)n, and we are determining the coefficients of (x + 1)n+1. Now, for any given i not 0 or n + 1, the coefficient of the xi term in the polynomial (x + 1)n+1 is equal to ai (the figure above and to the left of the figure to be determined, since it is on the same diagonal) + ai−1 (the figure to the immediate right of the first figure). This is indeed the simple rule for constructing Pascal's triangle row-by-row.

It is not difficult to turn this argument into a proof (by mathematical induction) of the binomial theorem. Since (a + b)n = bn(a/b + 1)n, the coefficients are identical in the expansion of the general case.

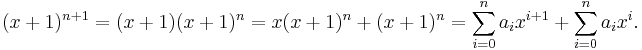

An interesting consequence of the binomial theorem is obtained by setting both variables x and y equal to one. In this case, we know that (1 + 1)n = 2n, and so

In other words, the sum of the entries in the nth row of Pascal's triangle is the nth power of 2.

Combinations

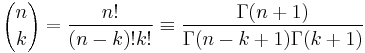

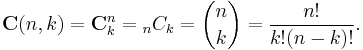

A second useful application of Pascal's triangle is in the calculation of combinations. For example, the number combinations of n things taken k at a time (called n choose k) can be found by the equation

But this is also the formula for a cell of Pascal's triangle. Rather than performing the calculation, one can simply look up the appropriate entry in the triangle. For example, suppose a basketball team has 10 players and wants to know how many ways there are of selecting 8. Provided we have the first row and the first entry in a row numbered 0, the answer is entry 8 in row 10: 45. That is, the solution of 10 choose 8 is 45.

Relation to binomial distribution and convolutions

When divided by 2n, the nth row of Pascal's triangle becomes the binomial distribution in the symmetric case where p = 1/2. By the central limit theorem, this distribution approaches the normal distribution as n increases. This can also be seen by applying Stirling's formula to the factorials involved in the formula for combinations.

This is related to the operation of discrete convolution in two ways. First, polynomial multiplication exactly corresponds to discrete convolution, so that repeatedly convolving the sequence {..., 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, ...} with itself corresponds to taking powers of 1 + x, and hence to generating the rows of the triangle. Second, repeatedly convolving the distribution function for a random variable with itself corresponds to calculating the distribution function for a sum of n independent copies of that variable; this is exactly the situation to which the central limit theorem applies, and hence leads to the normal distribution in the limit.

Patterns and properties

Pascal's triangle has many properties and contains many patterns of numbers.

Rows

- When adding all the digits in a single row, each successive row has twice the value of the row preceding it. For example, row 1 has a value of 1, row 2 has a value of 2, row 3 has a value of 4, and so forth.

- The value of a row, if each entry is considered a decimal place (and numbers larger than 9 carried over accordingly) is a power of 11 ( 11n, for row n). Thus, in row two, '1,2,1' becomes 112, while '1,5,10,10,5,1' in row five becomes (after carrying) 161,051, which is 115. This property is explained by setting x = '10' in the binomial expansion of (x + 1)row=n, and adjusting values to the decimal system. But x can be chosen to allow rows to represent values in any base - such as base 3; 1 2 13 ['1,2,1'] = 42 (16), 2 1 0 13 ['1,3,3,1'] = 43 (64) - or base 9; 1 2 19 = 102 (100), 1 3 3 19 = 103 (1000) and 1 6 2 1 5 19 ['1,5,10,10,5,1'] = 105 (100,000). In particular (see next property), for x = 1 place value remains constant (1place=1). Thus entries can simply be added in interpreting the value of a row.

- The sum of the elements of row m is equal to 2m−1. For example, the sum of the elements of row 5 is 1 + 4 + 6 + 4 + 1 = 16, which is equal to 24 = 16. This follows from the binomial theorem proved above, applied to (1 + 1)m−1.

- If rows are numbered starting with n = 0, the sum of the elements in the row is simply 2n, so row 0 adds to 20 = 1, row 1 adds to 21 = 2, etc.

- Some of the numbers in Pascal's triangle correlate to numbers in Lozanić's triangle.

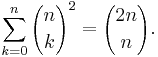

- The sum of the squares of the elements of row n equals the middle element of row (2n − 1). For example, 12 + 42 + 62 + 42 + 12 = 70. In general form:

- Another interesting pattern is that on any row m, where m is odd, the middle term minus the term two spots to the left equals a Catalan number, specifically the (m + 1)/2 Catalan number. For example: on row 5, 6 − 1 = 5, which is the 3rd Catalan number, and (5 + 1)/2 = 3.

- Another interesting property of Pascal's triangle is that in rows where the second number (immediately following '1') is prime, all the terms in that row except the 1s are multiples of that prime. This can be proven easily, since if

, then

, then  has no factors save for 1 and itself. Every entry in the triangle is an integer, so therefore by definition

has no factors save for 1 and itself. Every entry in the triangle is an integer, so therefore by definition  and

and  are factors of

are factors of  . However, there is no possible way

. However, there is no possible way  itself can show up in the denominator, so therefore

itself can show up in the denominator, so therefore  (or some multiple of it) must be left in the numerator, making the entire entry a multiple of

(or some multiple of it) must be left in the numerator, making the entire entry a multiple of  .

. - Parity: Start numbering the row from 0. To count odd terms in nth row, convert n to binary. Let x be the number of 1s in the binary representation. Then number of odd terms will be 2x.

Diagonals

The diagonals of Pascal's triangle contain the figurate numbers of simplices:

- The diagonals going along the left and right edges contain only 1's.

- The diagonals next to the edge diagonals contain the natural numbers in order.

- Moving inwards, the next pair of diagonals contain the triangular numbers in order.

- The next pair of diagonals contain the tetrahedral numbers in order, and the next pair give pentatope numbers.

The symmetry of the triangle implies that the nth d-dimensional number is equal to the dth n-dimensional number.

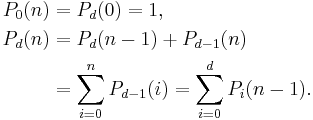

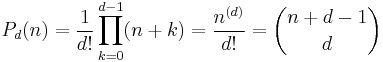

An alternative formula that does not involve recursion is as follows:

- where n(d) is the rising factorial.

The geometric meaning of a function Pd is: Pd(1) = 1 for all d. Construct a d-dimensional triangle (a 3-dimensional triangle is a tetrahedron) by placing additional dots below an initial dot, corresponding to Pd(1) = 1. Place these dots in a manner analogous to the placement of numbers in Pascal's triangle. To find Pd(x), have a total of x dots composing the target shape. Pd(x) then equals the total number of dots in the shape. A 0-dimensional triangle is a point and a 1-dimensional triangle is simply a line, and therefore P0(x) = 1 and P1(x) = x, which is the sequence of natural numbers. The number of dots in each layer corresponds to Pd − 1(x).

Calculating an individual row or diagonal by itself

This algorithm is an alternative to the standard method of calculating individual cells with factorials. Starting at the left, the first cell's value  is 1. For each cell after, the value is determined by multiplying the value to its left by a slowly changing fraction:

is 1. For each cell after, the value is determined by multiplying the value to its left by a slowly changing fraction:

where r = row + 1, starting with 0 at the top, and c = the column, starting with 0 on the left. For example, to calculate row 5, r = 6. The first value is 1. The next value is 1 × 5/1 = 5. The numerator decreases by one, and the denominator increases by one with each step. So 5 × 4/2 = 10. Then 10 × 3/3 = 10. Then 10 × 2/4 = 5. Then 5 × 1/5 = 1. Notice that the last cell always equals 1, the final multiplication is included for completeness of the series.

A similar pattern exists on a downward diagonal. Starting with the one and the natural number in the next cell, form a fraction. To determine the next cell, increase the numerator and denominator each by one, and then multiply the previous result by the fraction. For example, the row starting with 1 and 7 form a fraction of 7/1. The next cell is 7 × 8/2 = 28. The next cell is 28 × 9/3 = 84. (Note that for any individual row it is only necessary to calculate half (rounded up) the terms in the row due to symmetry.)

Overall patterns and properties

- The pattern obtained by coloring only the odd numbers in Pascal's triangle closely resembles the fractal called the Sierpinski triangle. This resemblance becomes more and more accurate as more rows are considered; in the limit, as the number of rows approaches infinity, the resulting pattern is the Sierpinski triangle, assuming a fixed perimeter.[8] More generally, numbers could be colored differently according to whether or not they are multiples of 3, 4, etc.; this results in other similar patterns.

- Imagine each number in the triangle is a node in a grid which is connected to the adjacent numbers above and below it. Now for any node in the grid, count the number of paths there are in the grid (without backtracking) which connect this node to the top node (1) of the triangle. The answer is the Pascal number associated to that node. The interpretation of the number in Pascal's Triangle as the number of paths to that number from the tip means that on a Plinko game board shaped like a triangle, the probability of winning prizes nearer the center will be higher than winning prizes on the edges.

- One property of the triangle is revealed if the rows are left-justified. In the triangle below, the diagonal coloured bands sum to successive Fibonacci numbers.

-

-

1 1 1 1 2 1 1 3 3 1 1 4 6 4 1 1 5 10 10 5 1 1 6 15 20 15 6 1 1 7 21 35 35 21 7 1 1 8 28 56 70 56 28 8 1

-

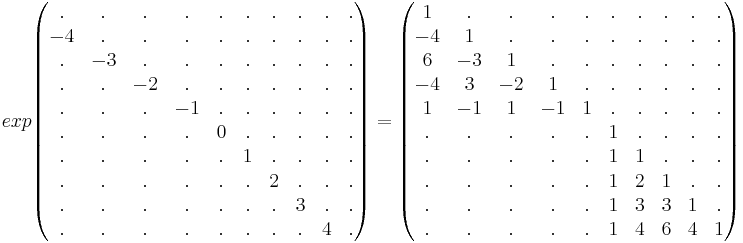

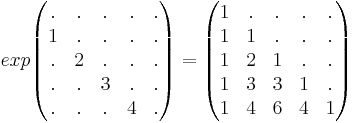

Construction as matrix exponential

Due to its simple construction by factorials, a very basic representation of Pascal's triangle in terms of the matrix exponential can be given: Pascal's triangle is the exponential of the matrix which has the sequence 1, 2, 3, 4, … on its subdiagonal and zero everywhere else.

Number of elements of polytopes

Pascal's triangle can be used as a lookup table for the number of elements (such as edges and corners) within a polytope (such as a triangle, a tetrahedron, a square and a cube).

Let's begin by considering the 3rd line of Pascal's triangle, with values 1, 3, 3, 1. A 2-dimensional triangle has one 2-dimensional element (itself), three 1-dimensional elements (lines, or edges), and three 0-dimensional elements (vertices, or corners). The meaning of the final number (1) is more difficult to explain (but see below). Continuing with our example, a tetrahedron has one 3-dimensional element (itself), four 2-dimensional elements (faces), six 1-dimensional elements (edges), and four 0-dimensional elements (vertices). Adding the final 1 again, these values correspond to the 4th row of the triangle (1, 4, 6, 4, 1). Line 1 corresponds to a point, and Line 2 corresponds to a line segment (dyad). This pattern continues to arbitrarily high-dimensioned hyper-tetrahedrons (known as simplices).

To understand why this pattern exists, one must first understand that the process of building an n-simplex from an (n − 1)-simplex consists of simply adding a new vertex to the latter, positioned such that this new vertex lies outside of the space of the original simplex, and connecting it to all original vertices. As an example, consider the case of building a tetrahedron from a triangle, the latter of whose elements are enumerated by row 3 of Pascal's triangle: 1 face, 3 edges, and 3 vertices (the meaning of the final 1 will be explained shortly). To build a tetrahedron from a triangle, we position a new vertex above the plane of the triangle and connect this vertex to all three vertices of the original triangle.

The number of a given dimensional element in the tetrahedron is now the sum of two numbers: first the number of that element found in the original triangle, plus the number of new elements, each of which is built upon elements of one fewer dimension from the original triangle. Thus, in the tetrahedron, the number of cells (polyhedral elements) is 0 (the original triangle possesses none) + 1 (built upon the single face of the original triangle) = 1; the number of faces is 1 (the original triangle itself) + 3 (the new faces, each built upon an edge of the original triangle) = 4; the number of edges is 3 (from the original triangle) + 3 (the new edges, each built upon a vertex of the original triangle) = 6; the number of new vertices is 3 (from the original triangle) + 1 (the new vertex that was added to create the tetrahedron from the triangle) = 4. This process of summing the number of elements of a given dimension to those of one fewer dimension to arrive at the number of the former found in the next higher simplex is equivalent to the process of summing two adjacent numbers in a row of Pascal's triangle to yield the number below. Thus, the meaning of the final number (1) in a row of Pascal's triangle becomes understood as representing the new vertex that is to be added to the simplex represented by that row to yield the next higher simplex represented by the next row. This new vertex is joined to every element in the original simplex to yield a new element of one higher dimension in the new simplex, and this is the origin of the pattern found to be identical to that seen in Pascal's triangle.

A similar pattern is observed relating to squares, as opposed to triangles. To find the pattern, one must construct an analog to Pascal's triangle, whose entries are the coefficients of (x + 2)Row Number, instead of (x + 1)Row Number. There are a couple ways to do this. The simpler is to begin with Row 0 = 1 and Row 1 = 1, 2. Proceed to construct the analog triangles according to the following rule:

That is, choose a pair of numbers according to the rules of Pascal's triangle, but double the one on the left before adding. This results in:

1

1 2

1 4 4

1 6 12 8

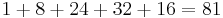

1 8 24 32 16

1 10 40 80 80 32

1 12 60 160 240 192 64

1 14 84 280 560 672 448 128

The other way of manufacturing this triangle is to start with Pascal's triangle and multiply each entry by 2k, where k is the position in the row of the given number. For example, the 2nd value in row 4 of Pascal's triangle is 6 (the slope of 1s corresponds to the zeroth entry in each row). To get the value that resides in the corresponding position in the analog triangle, multiply 6 by 2Position Number = 6 × 22 = 6 × 4 = 24. Now that the analog triangle has been constructed, the number of elements of any dimension that compose an arbitrarily dimensioned cube (called a hypercube) can be read from the table in a way analogous to Pascal's triangle. For example, the number of 2-dimensional elements in a 2-dimensional cube (a square) is one, the number of 1-dimensional elements (sides, or lines) is 4, and the number of 0-dimensional elements (points, or vertices) is 4. This matches the 2nd row of the table (1, 4, 4). A cube has 1 cube, 6 faces, 12 edges, and 8 vertices, which corresponds to the next line of the analog triangle (1, 6, 12, 8). This pattern continues indefinitely.

To understand why this pattern exists, first recognize that the construction of an n-cube from an (n − 1)-cube is done by simply duplicating the original figure and displacing it some distance (for a regular n-cube, the edge length) orthogonal to the space of the original figure, then connecting each vertex of the new figure to its corresponding vertex of the original. This initial duplication process is the reason why, to enumerate the dimensional elements of an n-cube, one must double the first of a pair of numbers in a row of this analog of Pascal's triangle before summing to yield the number below. The initial doubling thus yields the number of "original" elements to be found in the next higher n-cube and, as before, new elements are built upon those of one fewer dimension (edges upon vertices, faces upon edges, etc.). Again, the last number of a row represents the number of new vertices to be added to generate the next higher n-cube.

In this triangle, the sum of the elements of row m is equal to 3m − 1. Again, to use the elements of row 5 as an example:  , which is equal to

, which is equal to  .

.

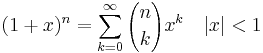

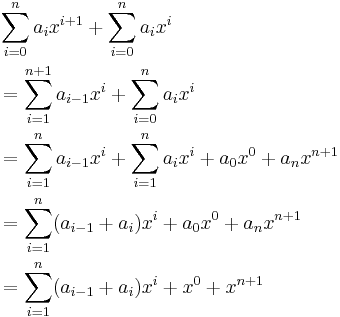

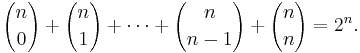

Fourier transform of sin(x)n+1/x

As stated previously, the coefficients of (x + 1)n are the nth row of the triangle. Now the coefficients of (x − 1)n are the same, except that the sign alternates from +1 to −1 and back again. After suitable normalization, the same pattern of numbers occurs in the Fourier transform of sin(x)n+1/x. More precisely: if n is even, take the real part of the transform, and if n is odd, take imaginary part. Then the result is a step function, whose values (suitably normalized) are given by the nth row of the triangle with alternating signs. For example, the values of the step function that results from

compose the 4th row of the triangle, with alternating signs. This is a generalization of the following basic result (often used in electrical engineering):

is the boxcar function. The corresponding row of the triangle is row 0, which consists of just the number 1.

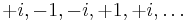

If n is congruent to 2 or to 3 mod 4, then the signs start with −1. In fact, the sequence of the (normalized) first terms corresponds to the powers of i, which cycle around the intersection of the axes with the unit circle in the complex plane:

Elementary cellular automaton

The pattern produced by an elementary cellular automaton using rule 60 is exactly Pascal's triangle of binomial coefficients reduced modulo 2 (black cells correspond to odd binomial coefficients).[9] Rule 102 also produces this pattern when trailing zeros are omitted. Rule 90 produces the same pattern but with an empty cell separating each entry in the rows.

Extensions

Pascal's Triangle can be extended to negative row numbers.

First write the triangle in the following form:

| m = 0 | m = 1 | m = 2 | m = 3 | m = 4 | m = 5 | ... | |

| n = 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 4 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ... |

Next, extend the column of 1s upwards:

| m = 0 | m = 1 | m = 2 | m = 3 | m = 4 | m = 5 | ... | |

| n = -4 | 1 | ... | |||||

| n = -3 | 1 | ... | |||||

| n = -2 | 1 | ... | |||||

| n = -1 | 1 | ... | |||||

| n = 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 4 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ... |

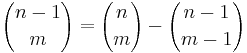

Now the rule:

can be rearranged to:

which allows calculation of the other entries for negative rows:

| m = 0 | m = 1 | m = 2 | m = 3 | m = 4 | m = 5 | ... | |

| n = −4 | 1 | −4 | 10 | −20 | 35 | −56 | ... |

| n = −3 | 1 | −3 | 6 | −10 | 15 | −21 | ... |

| n = −2 | 1 | −2 | 3 | −4 | 5 | −6 | ... |

| n = −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | ... |

| n = 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 4 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ... |

This extension preserves the property that the values in the mth column viewed as a function of n are fit by an order m polynomial, namely

.

.

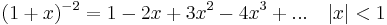

This extension also preserves the property that the values in the nth row correspond to the coefficients of  :

:

For example:

Another option for extending Pascal's triangle to negative rows comes from extending the other line of 1s:

| m = -4 | m = -3 | m = -2 | m = -1 | m = 0 | m = 1 | m = 2 | m = 3 | m = 4 | m = 5 | ... | |

| n = -4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = -3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | |

| n = -2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | ||

| n = -1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | |||

| n = 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ... |

Applying the same rule as before leads to

| m = -4 | m = -3 | m = -2 | m = -1 | m = 0 | m = 1 | m = 2 | m = 3 | m = 4 | m = 5 | ... | |

| n = -4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = -3 | -3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = -2 | 3 | -2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = -1 | -1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| n = 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ... |

| n = 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ... |

Note that this extension also has the properties that just as

,

,

we have

Also, just as summing along the lower-left to upper-right diagonals of the Pascal matrix yields the Fibonacci numbers, this second type of extension still sums to the Fibonacci numbers for negative index.

Either of these extensions can be reached if we define

and take certain limits of the Gamma function,  .

.

See also

- Bean machine, Francis Galton's "quincunx"

- Binomial expansion

- Euler triangle

- Floyd's triangle

- Leibniz harmonic triangle

- Multiplicities of entries in Pascal's triangle (Singmaster's conjecture)

- Pascal matrix

- Pascal's pyramid

- Pascal's simplex

- Proton NMR, one application of Pascal's triangle

- Star of David theorem

- Trinomial expansion

References

- ^ Peter Fox (1998). Cambridge University Library: the great collections. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780521626477. http://books.google.com/books?id=xxlgKP5thL8C&pg=PA13.

- ^ The binomial coefficient

is conventionally set to zero if k is either less than zero or greater than n.

is conventionally set to zero if k is either less than zero or greater than n. - ^ Pascal's Triangle | World of Mathematics Summary

- ^ a b A. W. F. Edwards. Pascal's arithmetical triangle: the story of a mathematical idea. JHU Press, 2002. Pages 30-31.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Bekr ibn Muhammad ibn al-Husayn Al-Karaji", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Karaji.html.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. (2003). CRC concise encyclopedia of mathematics, p.2169. ISBN 9781584883470.

- ^ (Fowler 1996, p. 11)

- ^ Wolfram, S. (1984). "Computation Theory of Cellular Automata". Comm. Math. Phys. 96: 15–57. Bibcode 1984CMaPh..96...15W. doi:10.1007/BF01217347.

- ^ Wolfram, S. (2002). A New Kind of Science. Champaign IL: Wolfram Media. pp. 870, 931–2.

Notations

- Fowler, David (January 1996). "The Binomial Coefficient Function". The American Mathematical Monthly 103 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/2975209. JSTOR 2975209.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Pascal's triangle" from MathWorld.

- The Old Method Chart of the Seven Multiplying Squares (from the Ssu Yuan Yü Chien of Chu Shi-Chieh, 1303, depicting the first nine rows of Pascal's triangle)

- Implementation of Pascal Triangle in Java – with conversion of higher digits to single digits.

- Pascal's Treatise on the Arithmetic Triangle (page images of Pascal's treatise, 1655; summary)

- Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (P)

- Leibniz and Pascal triangles

- Dot Patterns, Pascal's Triangle, and Lucas' Theorem

- Omar Khayyam the mathematician

- Info on Pascal's Triangle

- Explanation of Pascal's Triangle and common occurrences, including link to interactive version specifying # of rows to view

- Implementation of Pascal Triangle in SQL

![\,\mathfrak{Re}\left(\text{Fourier} \left[ \frac{\sin(x)^5}{x} \right]\right)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/818742bc110faa1a3a5abae4135228cb.png)

![\,\mathfrak{Re}\left(\text{Fourier} \left[ \frac{\sin(x)^1}{x}\right] \right)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8636cb36aaa201bcc47cfea7d94cee9c.png)